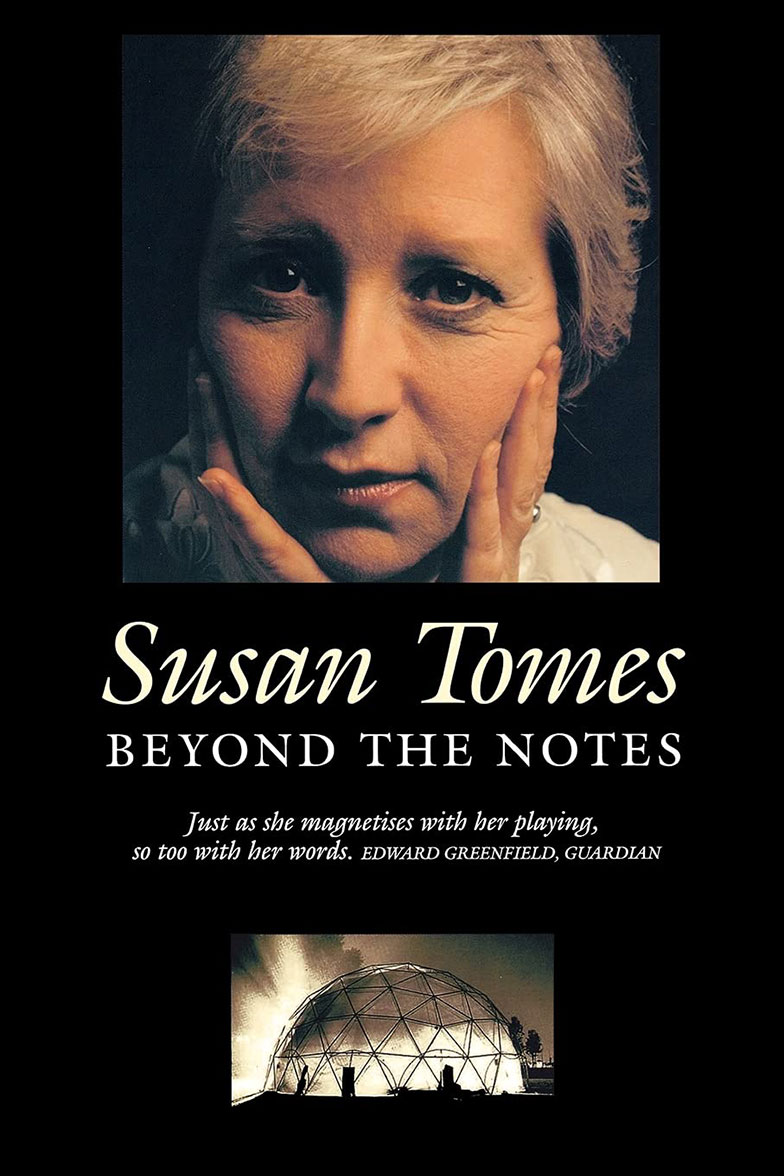

Susan Tomes is a pianist and writer. Renowned as a soloist and as a chamber musician, she’s also the author of seven books.

Susan Tomes has won numerous international awards as a pianist, both on the concert platform and in the recording studio, including several Gramophone Awards and the 2013 Cobbett Medal.

She is a solo pianist as well as a chamber musician. She has made fifty CDs and has been at the heart of the internationally admired ensembles Domus, the Gaudier Ensemble and the Florestan Trio with whom she won a Royal Philharmonic Society Award.

She is also the author of six acclaimed books. The Piano – a History in 100 Pieces (Yale, 2021) was a ‘Book of the Year’ in The Spectator and the Financial Times. Her seventh book, Women and the Piano – A History in 50 Lives, comes out from Yale University Press on 12 March 2024 and will be launched on that day with a solo concert by Susan in London’s Wigmore Hall.

My book comes out in the US today

I can't pretend to understand why it takes six weeks for a book published in the UK to come out in the US, but of course there are many practical issues to do with book publishing that I've never had much to do with. I imagine boxes of books slowly crossing the...

Get The Latest Posts

Interested in what Susan has to say about all things classical music? Subscribe below and whenever Susan writes a new blog post you will be notified by email. Simple!