Most people who learn piano will have come across Bach’s Two-Part Inventions, but their eyes may not have alighted on his Foreword. Mine hadn’t until the other day.

Most people who learn piano will have come across Bach’s Two-Part Inventions, but their eyes may not have alighted on his Foreword. Mine hadn’t until the other day.

‘Forthright instruction, wherewith lovers of the clavier, especially those eager to learn, are shown in a clear way not only 1) to learn to play two voices clearly, but also after further progress 2) to deal correctly and well with three obbligato parts, moreover at the same time to obtain not only good ideas, but also to carry them out well, but most of all to achieve a cantabile style of playing, and thereby to acquire a strong foretaste of composition.’

Bach seems to take it for granted that the student will be doing some composing of their own – a healthier attitude than we have today, where we tend to divide students at an early stage into players or composers – more’s the pity.

Bach’s attitude to ‘forthright instruction’ struck me as refreshingly different to current theories about ‘knowledge transfer’. A little while ago I went to a talk about the future of university education in which it was put to us that ‘teacher’ and ‘student’ should think of themselves as moving forward hand in hand on a journey of equals, each respecting what the other brings to the experience.

Whereas Bach just states that his instruction is forthright, clear, correct and will show the student how to play well and get good ideas about composition.

He backs up those claims with ‘inventions’ of wonderful range and clarity. Nothing is withheld: he shows exactly how to construct little themes of different characters and utilise them in clever and pleasing ways. His skill is so openly and generously displayed that one might think it is easy to copy him. Nevertheless, anyone who has tried will know that Bach has quietly avoided all kinds of traps which await the unwary. The way he fits things together, nothing awkwardly crammed in or left out, brings to mind the ‘mathematical bridge’ (such as the one in Queen’s College, Cambridge) which strikes the beholder as a lovely rounded arch, although it is made from straight pieces of timber.

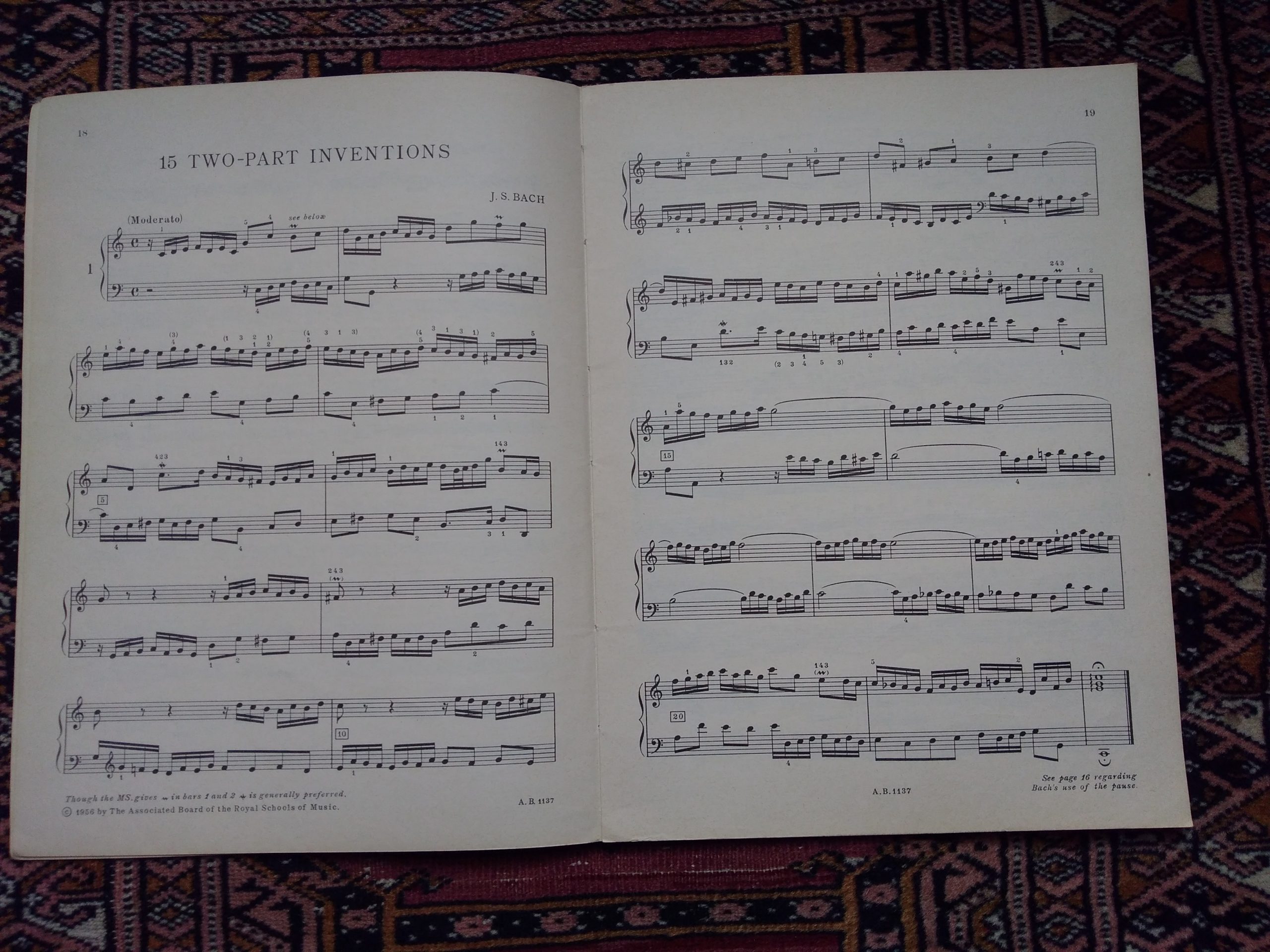

Invention no 1 in C major is the most famous. Its little theme, announced by the right hand, is answered in a lower octave by the left, beginning a dialogue in which one hand follows the other at half a bar’s distance. We are shown how to get the most out of this theme: inverting it (bars 3-4) so that every rise in pitch becomes a fall and vice versa; swapping the roles of right and left hand (bar 7); linking right-way-up and inverted versions to form a smoothly descending passage (bar 15). Moreover, he uses the four opening notes as a ‘cell’ in their own right. In notes twice as long, this cell becomes an ascending quaver motif in the bass (bars 3-4, bars 5/6), in the right hand (bars 11-12) and a descending motif in the left hand (bars 19-20). In bar 21 he flips the left hand motif back to its original format so that we suddenly recognise it as the opening theme, or at least the first six notes of it (CDEFDE).

A century later, the technique of one ‘voice’ following another at a distance was given a different slant by Romantic composers, particularly Schubert and Schumann, to conjure up the illusion of the Doppelgänger or mysterious double which dogs the narrator’s footsteps, trailing him like a shadowy version of himself. This is not how Bach uses the technique of ‘imitation’. With him, it is a demonstration of the art of civilised dialogue – considerate, balanced and wide-ranging, with a touch of grave humour when things turn upside-down.

Hi Susan,

I love the 2-part inventions! I was introduced to them when I started playing piano in college in the 1960s. Then I didn’t play for decades. Now I’m retired and practicing again, and for me the inventions are musically fascinating while technically feasible.

But honestly, I enjoy the major-key inventions much more than the minor ones, so I’ve been “revising” the minor ones. I recast #4 in d minor from 3/4 time to 6/8 time, which seems more cheerful. And I recast #11 from g minor to G major, definitely more cheerful. This isn’t really “composing” but there are some fun challenges and I sure am learning a lot.

Thanks for your wonderful website and blog. I have some old CDs of Domus and your playing is wonderful, also.

Sincerely,

Rita Buchanan

Rita, I’m sorry I didn’t realise your comment was waiting to be ‘admitted’ to my website until now. It’s been a complicated week! Anyway, thank you for your comments – I think it’s a great idea to recast pieces in different time-signatures as you describe. I haven’t come across anyone who puts the minor Inventions into major keys, but as you say, one can learn a lot from that kind of exercise!