It’s been a turbulent week, and I have found some distraction in playing through a volume of Grieg’s Lyric Pieces. I’ve always liked them, though I admit I knew only the more famous pieces, and only recently discovered that there are many more – all worth getting to know.

It’s been a turbulent week, and I have found some distraction in playing through a volume of Grieg’s Lyric Pieces. I’ve always liked them, though I admit I knew only the more famous pieces, and only recently discovered that there are many more – all worth getting to know.

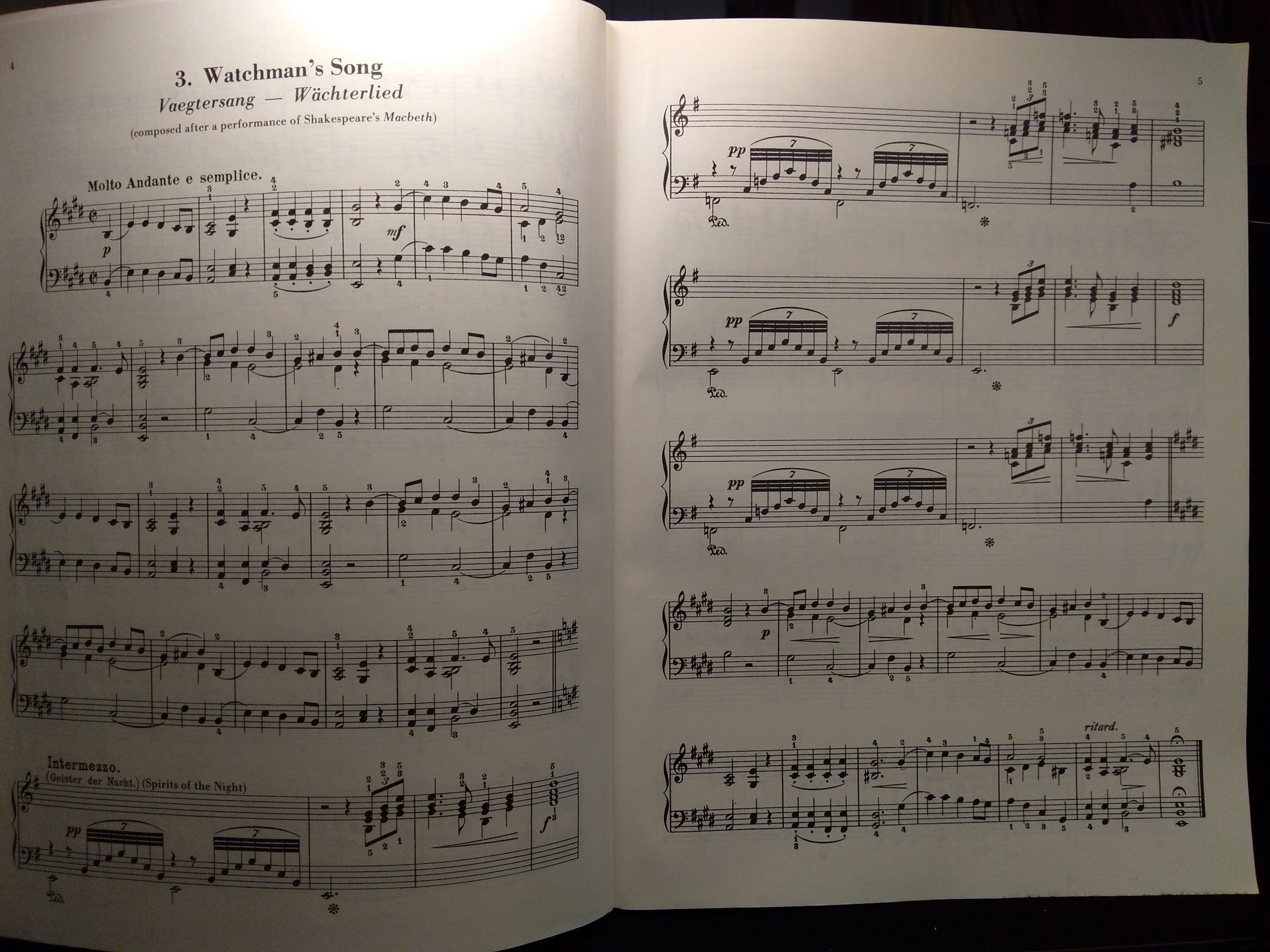

The first set, opus 12, contains a little piece called ‘Watchman’s Song’, over which Grieg noted that it was written after seeing a performance of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Over the middle section, Grieg wrote ‘Spirits of the Night’. Which would lead us to expect something atmospheric and scary – wouldn’t it?

Actually, the Watchman’s Song consists of two verses of a tranquil hymn in E major, separated by a short ‘intermezzo’ of gently rippling arpeggios and distant fanfares. ‘Spirits of the Night’ seems too bold a stage direction for a few bars arousing the merest hint of unease.

It’s quite amusing to wonder what would happen if you gave the ‘Watchman’s Song’ to someone who knew nothing of Macbeth and asked them to imagine what sort of play this represented…!

All of which raises some interesting questions. First of all, I suppose one would have to ask what sort of production Grieg had seen, and how it affected him. We know he saw the version of Macbeth devised by the German playwright Schiller. Surely this conveyed all the tragic and fateful qualities of the original. Yet the play, whose sinister atmosphere has provoked long-lasting superstitions in the theatre world, seems not to have ruffled Grieg’s feelings. So perhaps it was a terrible performance? It’s hard to imagine that one could see Macbeth and come out with nothing more than the desire to write a cheery little tune for the watchman. Or was Grieg was so terrified that the watchman was the only character he could bear to describe?

Anyway, what watchman? To my recollection, there isn’t a watchman in Macbeth, at least not named as such. There’s a porter, who diverts proceedings by telling the audience how he imagines being the doorman at the gate of hell. There’s a messenger who comes to Dunsinane to tell Macbeth that he thinks he saw ‘a moving grove’ coming towards the castle. Is one of these the watchman? Or did Schiller perhaps put one in? If so, why was he the character who stuck in Grieg’s mind? And what about the ‘spirits of the night’ – did they not inspire any terror?

It can’t be that Grieg lacked imagination, because many of his Lyric Pieces are beautiful little cameos conjuring up all sorts of delicate emotions. How intriguing it would have been to hear his take on the Witches, Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking, or the drunken Porter!

Grieg’s family emigrated to Norway from Scotland – the family surname originally having been spelled Greig, as is the custom in Scotland. Funnily enough, in 2010 the Scottish contemporary playwright David Greig wrote a play called Dunsinane – a kind of sequel to Macbeth. So the play links Grieg and Greig – perhaps they have a connection?

You’ve just solved a mystery for me! As a child I played from an ancient volume of piano/violin arrangements of famous classical pieces. The Watchman’s Song really puzzled me – unusually, it summoned up no picture or scene in my head. Thanks to you, at last I understand the context of its composition, if not the piece itself.

This is intriguing. Thank you! – I couldn’t resist, had to look up Schiller’s version of Macbeth. Apparently the replacement of the porter’s monologue is the most conspicuous changes Schiller made! And he did replace it with a pious morning song. This is my translation, apologies in advance:

The sombre night has vanished,

the lark is singing,

the sun appears in glory

rising into the sky.

It shines into the splendour of the king’s chamber,

it shines through the beggar’s roof,

and what was hidden in the night,

It makes it known and manifest.

(Stronger knocking on the door)

Knock! Knock! Be patient out there, whoever it may be! Let the porter finish his morning song. A good day starts with the praise of god; there’s no business as urgent as prayer. (Continues singing.)

Praise unto the lord, and gratitude,

to him who watched over this house

with his holy regiments,

who graciously wished to protect us.

‘Tis true, many have closed their heavy eyes,

never to open them to the light anymore;

so, let him rejoice who, revived anew,

raises his gaze to the sun.

Hartmut, thank you so much for providing this information! I had no idea that Schiller had replaced the cheeky porter’s speech with an uplifting ‘morning song’, but now I understand much better why Grieg wrote his little piano piece. How interesting! I wonder why Schiller made the change – perhaps he thought the German audience would not be amused by the porter’s remarks on drink and its effects?

Mary, that’s a very interesting recollection. Did you read Hartmut Kuhlmann’s explanation (in the adjacent comment) of how Schiller changed the porter’s scene into a pious morning song? Hence the tone of Grieg’s little piece, I suppose.

Susan, I had to read a bit in order to be able to reply to your question … In 1784, Schiller wrote an essay which became famous, “Die Schaubühne als moralische Anstalt betrachtet”, the theatre regarded as a moral institution. According to this, the theatre is not supposed to be mere entertainment. Instead, it has the function of educating and elevating the audience. It seems that Schiller’s adaptation of Macbeth is quite in line with this idea. He took things out which he thought would be too cruel, or too grotesque. And he eliminated elements that don’t comply with what he expected to be the ethical message. Replacing the porter’s monologue, from this point of view, seems just consistent with his overall strategy – another example is his treatment of the three witches which in his interpretation turn into some kind of goddesses of destiny. Körner, a contemporary of Schiller’s, criticised this treatment of the witches, to which Schiller replied: “it seemed necessary to me, because the bulk of the audience has too little attention, and one has to think ahead for them”.

Now, here’s an author who really loves and appreciates his audience …

Thanks to Hartmut’s delving I now understand why I disliked the ‘tone’ of the piece! I felt a bit ‘shouted at’ (as in ‘lectured’) by the music and couldn’t understand why.

Thank you for the information! I have a piano student who will be playing “Watchman’s Song” on his recital next week, and both he and I have been curious about the origins of this beautiful work.

Thank you Kevin – I wrote this blog post a couple of years ago and am pleased to hear that someone has found it useful!

I also came across this post while curious about the background of this piece, and found it (and Hartmut’s further delving) interesting and useful, thank you! But I mainly wanted to comment to say that the idea of Grieg leaving the play “so terrified that the watchman was the only character he could bear to describe” made me laugh out loud. Poor guy!

Very interesting topic!

For sometime I thought it was inspired by HAMLET and I want to say that it made sense to me: the watchman’s song is naive, almost folkloric, and then… I must say I disagree about the nature of that middle section: it sounds transcendental and ghostly to me! Compare with the supernatural appearence of death in Schubert’s song “Death and the Maiden”: it doesn’t need to sound “gloomy” to convince as something from the other world. I remember also Richard Strauss’s “Death and Transfiguration”: its more poisoning theme, quoted decades later in the last of his “Four Last Songs”, is mysterious, but not exacly “dark”.

Now, with this proper context that it refers actually to Macbeth, I must say that middle section still sounds mysterious, supernatural, transcendental, so much different from the watchman’s hymn, that is, from the other world.

Thank you Leonardo – interesting to read your reply three years after I wrote the post!

You make a good point – that ‘it doesn’t need to sound ‘gloomy’ to convince as something from the other world.’