Volume One of Mendelssohn’s complete solo piano music is on my music desk. Mendelssohn was an astonishingly precocious chap and wrote some of his finest music – the Octet for Strings, for example – when still a teenager. He was first and foremost a pianist, so it’s intriguing that his earliest masterpiece was not for his own instrument.

Volume One of Mendelssohn’s complete solo piano music is on my music desk. Mendelssohn was an astonishingly precocious chap and wrote some of his finest music – the Octet for Strings, for example – when still a teenager. He was first and foremost a pianist, so it’s intriguing that his earliest masterpiece was not for his own instrument.

In his mid-teens he wrote a huge amount of piano music, much of it inspired by Bach and Beethoven. He was studying counterpoint and fugues, which often found their way into his pieces. Right from the start, he had an easy command of the keyboard. Swathes of notes are offered with a light touch. Some of those early pieces might have benefitted from an editor’s red pencil, but there’s something sweet about the way he feels he can have your attention for as long as it takes. You can just imagine him as a teenager.

At the age of 16 he wrote Seven Characteristic Pieces opus 7 (1825), a collection of etudes, wistful little ‘mood pieces’ , and complicated fugues dedicated to his piano teacher. You can feel him trying out styles he later used to compelling effect in his Songs without Words and his piano chamber music.

His choice of the word ‘Characteristic’ is puzzling. Did he mean characteristic of Bach, for example? Or did he just mean that each piece had a distinct character? I smiled to remember a tale I once heard about a Hollywood film session player in the early 20th century. The boys were about to record a bit of Cuban dance music for a cartoon. One of the players was caught on tape calling out to the producer, ‘Is this supposed to be typical?’

So I suppose Mendelssohn’s pieces are supposed to be typical.

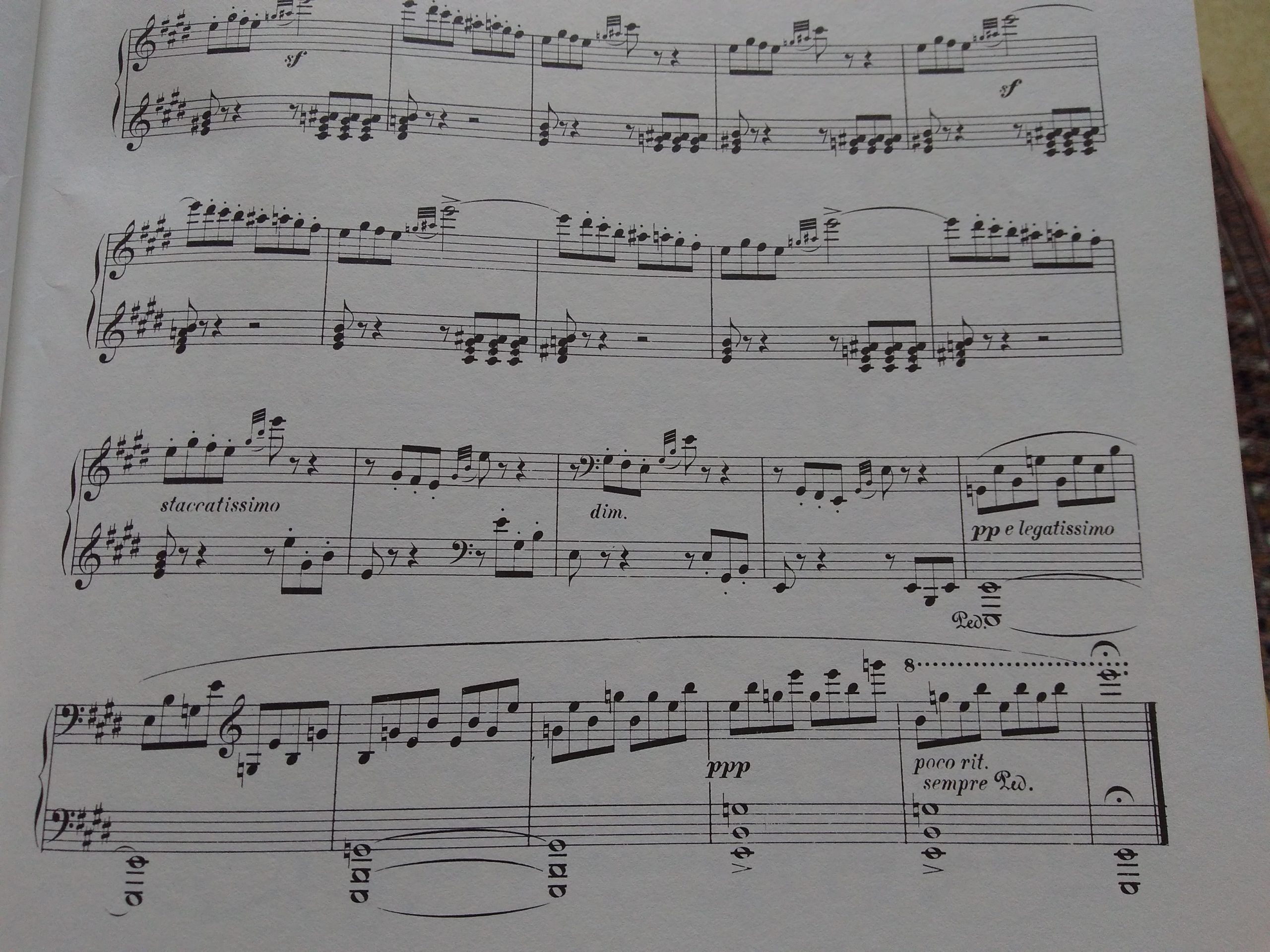

I played all the way to the final one before I heard the spark we associate with Mendelssohn at his best. No 7, ‘light and airy’, is a scherzo of the kind he was so good at (and in E major, a key in which he was so much at home). For much of the piece, the right and left hands alternate as they patter about the keyboard. On the final page, a surprise: as we approach what looks like being a throwaway ending, he pulls the rug from under our feet by making an unexpected turn to a minor key and a serious mood. A deep bass E tolls as the piece’s only legato arpeggio glides up into the high treble, slows down, and hovers there.

It’s quite common to find a piece in a minor key ending in the major. Much less usual is to find a long and cheery piece ending abruptly in a minor key.

This twist in the tale was quite exciting. Many of the previous pieces in the set had seemed a bit like composition exercises, but suddenly I felt I was hearing Mendelssohn’s true imaginative voice.

0 Comments