As the Brexit story accelerates, musicians are still in the dark about what will happen to their freedom of movement after we leave the EU. For two and a half years now I have been listening to colleagues and students worrying about whether they will still be able to study here, or if they are from the UK, whether they will still be able to afford to study in cities like Berlin, Vienna, Amsterdam or Brussels where they are happy. Will the Erasmus scheme still be open to UK students? What will happen to student fees? Will they still be able to go in for that competition in Paris or Rome? I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve asked young musicians whether we might meet again on the same course next year, only to be told, ‘I have no idea. Will we still be eligible?’

As the Brexit story accelerates, musicians are still in the dark about what will happen to their freedom of movement after we leave the EU. For two and a half years now I have been listening to colleagues and students worrying about whether they will still be able to study here, or if they are from the UK, whether they will still be able to afford to study in cities like Berlin, Vienna, Amsterdam or Brussels where they are happy. Will the Erasmus scheme still be open to UK students? What will happen to student fees? Will they still be able to go in for that competition in Paris or Rome? I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve asked young musicians whether we might meet again on the same course next year, only to be told, ‘I have no idea. Will we still be eligible?’

Young professional musicians are the group I most often work with. They are desperate for clarity. Many of them are from European countries. They love London and were thinking of staying here, getting jobs here, basing their performing careers here, settling down with partners they met here. Now there’s talk of a minimum salary level of £30,000 being required of European migrants after Brexit. That would rule out most of the young musicians I know. When you are paid £128 for an orchestral concert it takes a long time to earn £30,000.

I occasionally serve on the jury of international competitions. The other day, when I was talking to one of them about the extra paperwork that might be required for me after Brexit, an administrator ‘jokingly’ remarked that it might be easier for them just to choose their jury members from European countries. I’m one of those jury members now, but not for much longer.

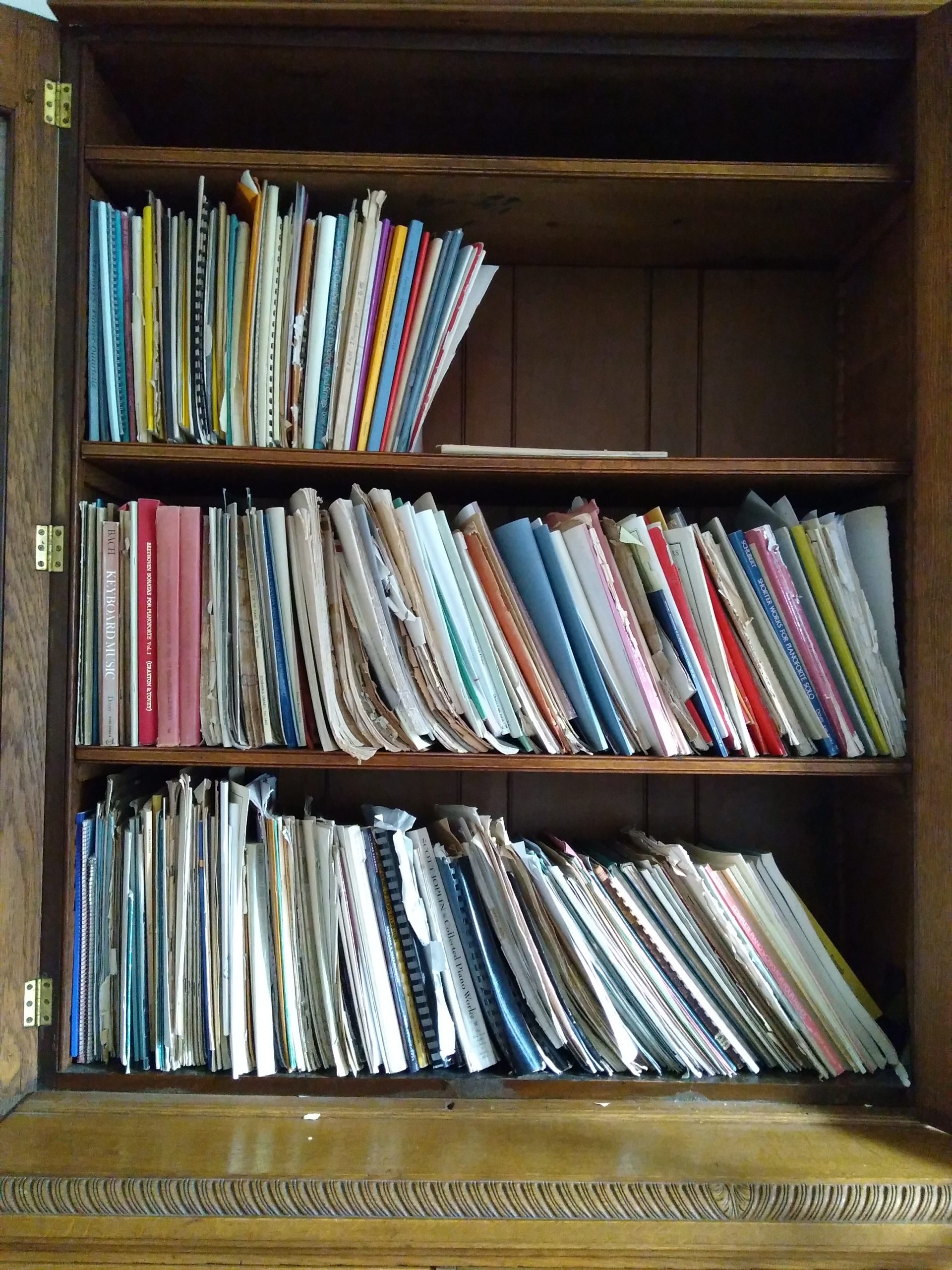

When I think back over my working life I realise that one of my greatest pleasures has been discovering other European countries and their cultures. I suppose I was predisposed to like them because most of my favourite composers (see photo) had lived there. My professional life began more or less as the UK joined the EU and travel to other European countries became ‘frictionless’. As I ventured further afield, my eyes and ears were opened to other ways of doing things. Breathing the same air as Mozart, Schubert or Debussy made everything easier to imagine, their music easier to ‘speak naturally’. A bit of extra paperwork won’t stop us going to those places, of course, but it feels like a step backwards.

As an American, it’s difficult for me to know all the reasoning behind the Brexit decision, but it seems to make about as much sense as the results of out last presidential election here. This nationalistic fervor hurts art and music the most. We who need mobility to make a living and to learn what we need to are going to feel the effects of such territorial imperatives for a long time, and the public will eventually feel that loss.

Well expressed! Thank you Alicia.