In a second-hand bookstore last week I came across the cello part of Beethoven’s late string quartets. Just the cello part – the other parts were missing. It was cheap, and I bought it out of curiosity.

In a second-hand bookstore last week I came across the cello part of Beethoven’s late string quartets. Just the cello part – the other parts were missing. It was cheap, and I bought it out of curiosity.

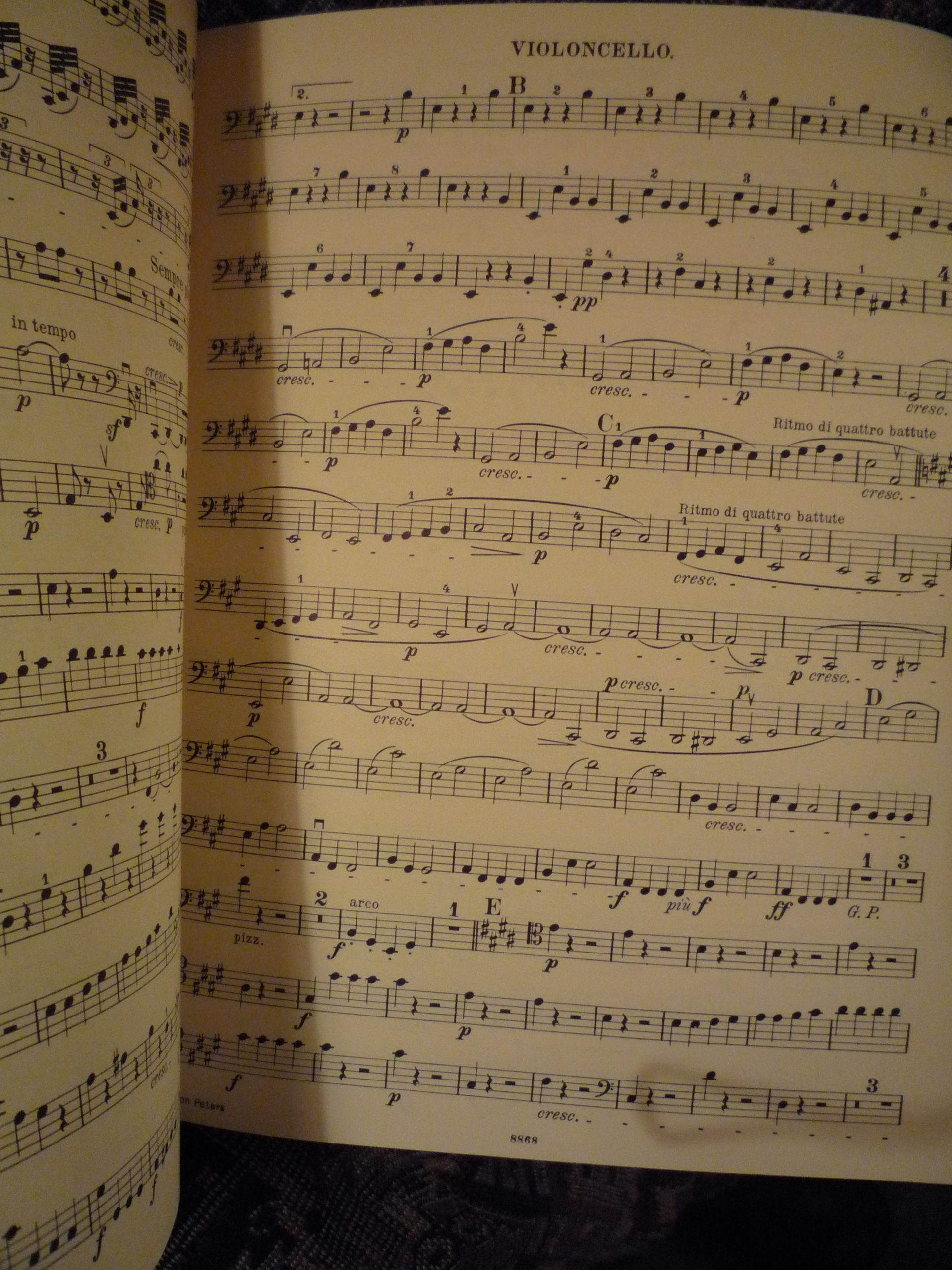

Looking through it when I got home, I was struck by how impossible it is to guess, from the cello part alone, what else is happening in the music, let alone how monumental it is. The single bass part looked simple and straightforward, almost dull (see photo). Yet of course in context it is nothing of the kind.

I know these quartets by ear, so in some places I could supply the rest in my imagination. But what if you had never heard the quartet performed? Having only a single part would keep you totally in the dark. You’d be dumbfounded when you heard the other parts leap into life in all their complexity.

I started to wonder whether I could think of any other art form where the performer has so little information when they begin learning their own part. Actors have the whole script of the play when they start learning their lines, don’t they? But Bob told me it wasn’t always so: in Shakespeare’s day, actors were often handed just their own part. Until rehearsals began, they had no notion of anyone else’s lines. The rehearsal process must have been a continuous source of surprise for actors as they realised the significance of what they had to say. That’s the only analogy we could think of for the single parts which many musicians still use today.

The situation is different for pianists, who by tradition have everyone else’s parts printed in small font in the piano score. Right from the beginning the pianist can see the full picture – though it’s true that sometimes, when rehearsals begin, the actual sound still comes as a surprise in some indefinable way.

As a cellist, I really appreciate this sympathy! It is grim practising chamber music parts when you have no (straightforward) way of knowing how your part is going to fit with the rest. Maybe the new digital age will give us an alternative to those cello-only printed parts we use now. The only good thing is that we only have a fraction of the page turns a pianist must negotiate!

I have been struck on several occasions, reading your musings and books, of the different perspectives of different musicians, and particularly instrumentalists and singers. It’s interesting that much of the most interesting writing is by instrumentalists, and pianists in particular – I am still looking for the equivalent from a singer.

I used to play the cello, and so experienced this piecemeal thinking first hand. I loved playing chamber music particularly because you started to hear and feel the combination of instruments, though it seems that the single line score is more a convenience than anything else.

These days much of my musical participation is through singing, where, historically, part books for singers would have been just like the cello part, showing only a single part. Nowadays we do get to see the whole score, which makes such a difference in showing what others are doing, both to allow correct entries, but also to see points of imitation or dissonance. It’s hard to imagine managing without.

I read this post several months ago, and similar musings in _Beyond the Notes_ some time before that, but it’s taken me until now to put down my own thoughts. I’m a singer, and like your previous respondent, often sing in ensembles where we take it for granted that each individual will have a complete vocal score with all of the other parts laid out in front of him or her (not having to handle instruments, we can of course manage frequent page-turns without much difficulty). But a while ago I was singing Renaissance madrigals with some aficionados of historically-informed performance practice, who were quite insistent on wanting to experiment with singing from part-books. I was resistant to the idea, making the case that full vocal scores enabled us to be more aware of each other, and of the musical whole, and that there was no need for us to return to the notational conventions of an era when printing technology was less refined, and paper scarcer. But my colleagues dug their heels in, and told me quite forcefully that, by clinging to my modern full score, I was allowing myself to rely on my eyes rather than really listening to the music, and missing out on an opportunity to feel the music unfolding in a different way. Our subsequent experiments in reading the music from part books were, I’m afraid, inconclusive – our rehearsals instantly became much more inefficient and time-consuming, as it was now much more difficult to rescue the music once a performer had come adrift; but some of my colleagues still claimed that they were hearing and feeling the music in longer lines and bigger shapes, and that they felt liberated from the supposed tyranny of the barlines in a modern vocal score.