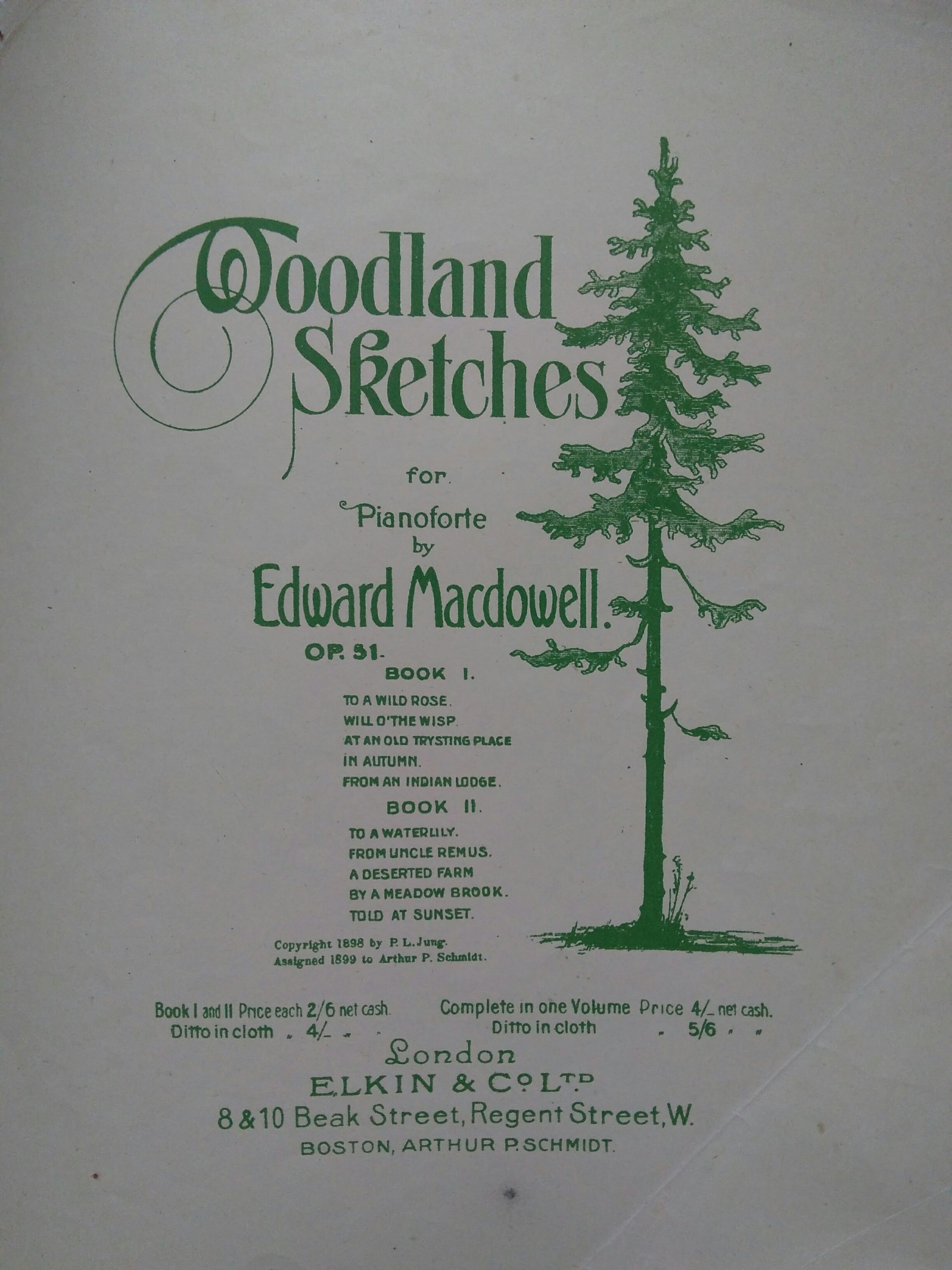

Over the years I’ve acquired various bits of piano music as gifts when friends were throwing away stuff they never played. That’s how I came to have Edward MacDowell’s Woodland Sketches. Most people know the first number, ‘To a Wild Rose’, but the rest of the set is obscure, at least here in the UK.

Over the years I’ve acquired various bits of piano music as gifts when friends were throwing away stuff they never played. That’s how I came to have Edward MacDowell’s Woodland Sketches. Most people know the first number, ‘To a Wild Rose’, but the rest of the set is obscure, at least here in the UK.

Edward MacDowell (1860-1908) was one of the first wave of American composers to travel to Europe to study with the European masters considered the leading lights of classical music. In Paris he was a fellow student of Debussy’s. Then he went to Germany and studied piano and composition in Frankfurt.

In Frankfurt, he played the piano in a special performance of Schumann’s Piano Quintet when the composer’s widow Clara Schumann came to visit the conservatory with Liszt in 1880. Schumann had a genius for little cameos, and MacDowell was on his wavelength. I imagine that Schumann’s Waldszenen (Forest Scenes) was a model for Woodland Sketches.

Liszt also makes his mark on the Sketches. The year after meeting Liszt, MacDowell travelled to Weimar to play to the great man in his home. Liszt liked him and tried to help him find a publisher for his music. Liszt’s famous virtuoso showpiece ‘Feux Follets’ (Fireflies) was surely an inspiration for MacDowell’s rather more approachable ‘Will o’the Wisp’.

After his years in Europe, MacDowell returned to New York where he became the first professor of music at Columbia University. He found it intensely stressful to run a music department in an institution where not everyone thought music deserved to be on the curriculum. One of his students remembered being told by the Dean that music was ‘a mental discipline less rigorous and possibly less rewarding than poker’. MacDowell longed for the summer holidays when he could retreat to his peaceful summer home in Peterborough, New Hampshire and write music.

‘To a Wild Rose’ was retrieved from the wastepaper basket by Mrs MacDowell, who uncrumpled it, played it on the piano and found it charming. MacDowell was persuaded to let it live. And a good thing she did, because its simple beauty has appealed to generations of young pianists.

MacDowell’s use of Italian musical terms is inventive. His pieces contain some directions I’ve never seen elsewhere: ‘Torvo, con enfasi’ (Sternly, with emphasis); ‘Con moto sonnolento, ondeggiantamente’ (with sleepy motion, undulating); ‘Quistionaramente’ (questioningly). Soon, American composers would switch to using their native language for musical directions, and one can sense MacDowell tying himself (and others) in knots with the effort to use Italian when he could have expressed himself more clearly in plain English.

One thing which gives his piano music an ‘American’ flavour is his use of melodies said to be those of American Indians or of African-Americans. ‘From an Indian Lodge’, features a solemn ‘Red Indian’ melody he had seen noted down. ‘From Uncle Remus’ has the same sort of capering humour one finds in Debussy’s ‘Golliwog’s Cakewalk’. Echoes of sad ‘negro spirituals’ float through ‘A Deserted Farm’.

Today these evocations may seem in doubtful taste, but we must remember that even Dvorak, when he was in America, made a point of including spirituals and American Indian tunes in his music as a way of preserving them. ‘The music of the people is like a rare and lovely flower growing among encroaching weeds’, Dvorak wrote. ‘Thousands pass it while others trample it underfoot, and the chances are that it will perish before it is seen by the one discriminating spirit who will prize it above all else.’

What a lot of interesting background – thank you for all these side shoots!

I recently heard a R3 person talking about an African-American musician who introduced Dvorak to the music but explicitly made the point that Dvorak absorbed the essence of it but all the instances in his music were his compositions.Sorry not to be more precise on sources.

That’s interesting, Andrew, thank you for adding this.