It’s amazing how often the last movements of multi-movement works are a disappointment. Time and again, my chamber groups would bemoan the fact that the finale of whatever we were rehearsing wasn’t as inspired as the rest of the piece.

It’s amazing how often the last movements of multi-movement works are a disappointment. Time and again, my chamber groups would bemoan the fact that the finale of whatever we were rehearsing wasn’t as inspired as the rest of the piece.

I once observed that composers could have solved the problem by just not writing last movements (a thought which still entertains me).

Finales traditionally follow certain formulas, the most popular being the jolly dance which comforts the listener after the complications of the preceding movements.

Another formula is the turn, sometimes the tongue-in-cheek turn, to the academic. Quite a few last movements feature baroque-style fugal passages and other solemn devices which seem designed to prove that even at this late stage, the composer had another style up his sleeve.

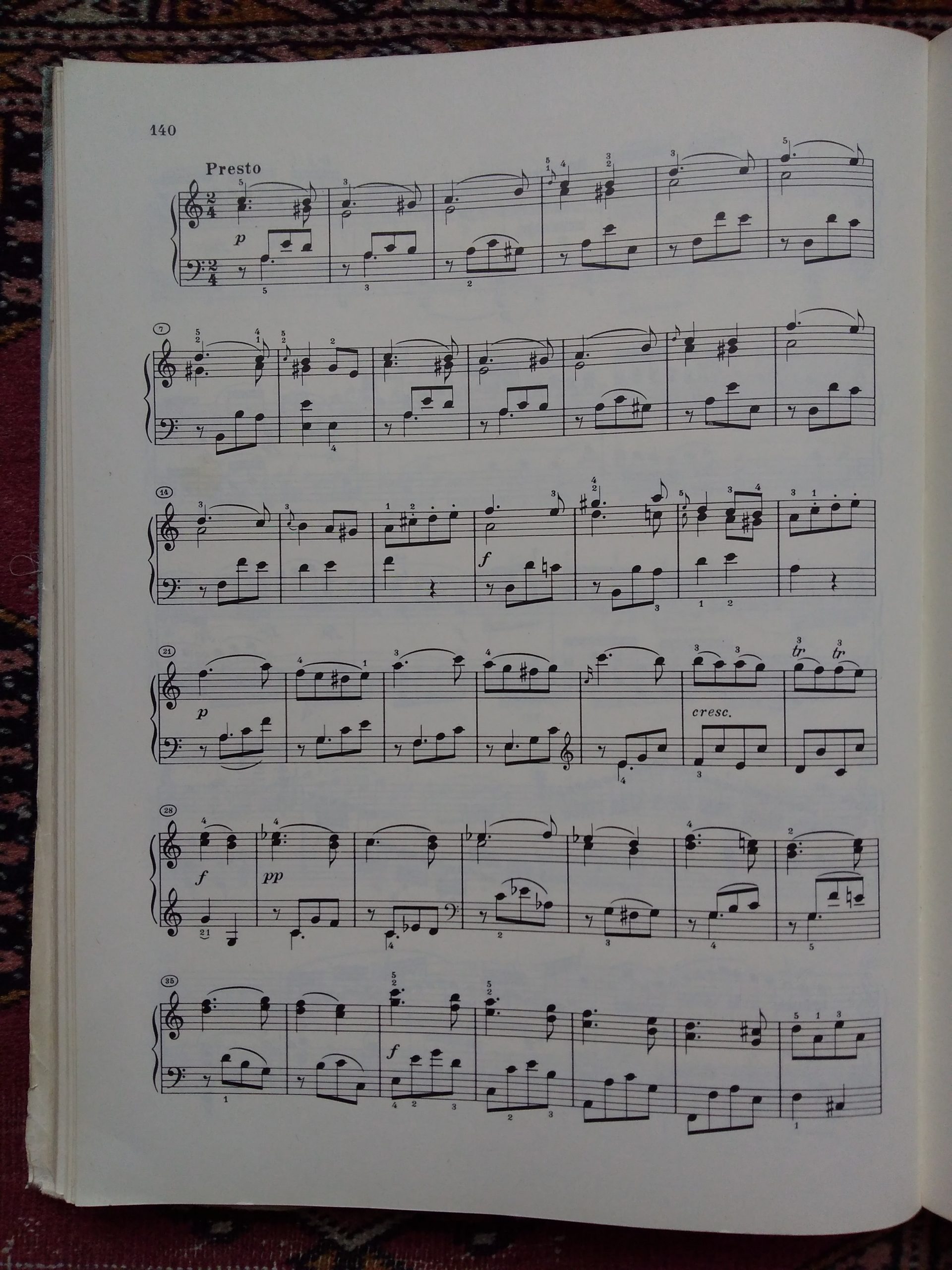

Now and then one comes across a type of last movement of which I’m particularly fond – the mysterious finale. The first one I can think of in Mozart’s A major piano sonata K310 (see photo). It’s marked ‘Presto’ and is fast and quiet for most of the movement. It’s written mainly in simple crotchets and quavers, but in the opening theme, the left hand is silent on the first quaver of each bar, only coming in a moment later with the note which confirms the harmony. This gives an unstable quality to the music. There’s very little rhythmic variation in the whole movement (a type of piano writing which Schubert also used – eg in the finale of his A minor sonata D845).

Coming after the grand, bravura opening movement and the operatic slow movement of K310, Mozart’s quiet final Presto is like some kind of wind getting up and blowing all the ardour away.

Beethoven does the same thing in the finale of his D minor piano sonata opus 31 no 2, ‘Tempest’. Here too, the drama of the earlier movements is made to look rather overblown by the quiet spinning-wheel motion of the finale. Beethoven’s theme is rather like Mozart’s, both featuring a falling minor third, so perhaps Mozart was the model.

A striking example of a mysterious last movement is in Chopin’s B flat minor piano sonata. Its finale is a ‘perpetuum mobile’ with a unique character – restless, obsessive, dangerously quiet. Chopin, who usually marked where he wanted the pedal to be used, didn’t mark any pedal here (except in the last bar). Therefore his finale sounds like several pages of slightly deranged muttering, or some kind of dark prophecy. It certainly puzzled lots of people, even friends who usually admired him, like Schumann and Mendelssohn. But time has allowed us to appreciate its visionary qualities. It’s a vision which, perhaps, Mozart also had.

Yes – can see how entertaining the idea there not being last movements might be!