I’m trying to learn some new pieces during this lockdown. My latest project is Chopin’s Fourth Ballade. I’ve half-known it for years, but never tried to learn it properly. It requires quite a big stretch, which I don’t have, and I’ve never been sure I could get my hands round some of the chords at speed. Anyway, why not try? Nobody except the cat is feeling critical.

I’m trying to learn some new pieces during this lockdown. My latest project is Chopin’s Fourth Ballade. I’ve half-known it for years, but never tried to learn it properly. It requires quite a big stretch, which I don’t have, and I’ve never been sure I could get my hands round some of the chords at speed. Anyway, why not try? Nobody except the cat is feeling critical.

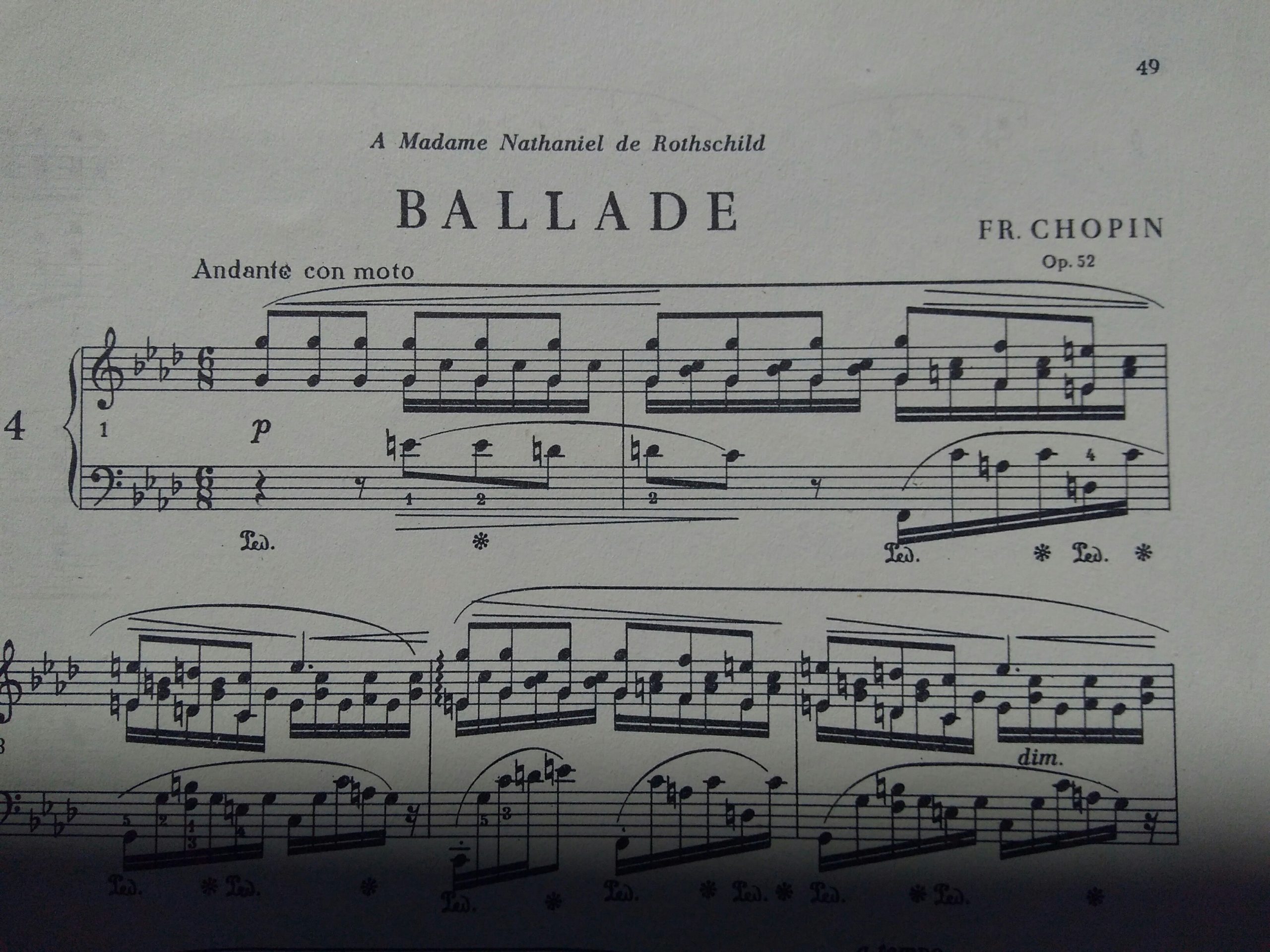

The very opening presents an interesting challenge. As you’ll see from the photo, it opens with a crescendo in the right hand and, simultaneously, a diminuendo in the left hand. The intended effect, I imagine, is that something in the left hand is dying away just as something in the right hand is getting started. It’s a genius idea, actually – giving the impression that the curtain has just been raised on a conversation already in progress. As the curtain rises we’re hearing the last ‘remark’ made by the left hand.

But how hard it is to do! To start quietly in the right hand with the aim of getting gradually louder, while starting more loudly in the left hand and getting gradually quieter (and both in an appropriately poetical way) feels a bit like those games where you have to pat the top of your head with one hand while making circles on your tummy with the other hand. It requires, as the Irish writer Flann O’Brien might say, ‘a wisdom not taught in the National Schools’.

It made me realise how often the instructions for volume, or volume changes in piano music are intended to apply to both hands at once. It’s natural, of course, for the two hands to co-operate in this way, so no wonder it’s the default setting for composers. Crescendos and diminuendos usually apply to both hands, harnessed together to create a single effect.

One does often come across contrasting planes of loudness, for example a melody played strongly in one hand while the other plays a quiet accompaniment. But these tend to be sustained passages where the pianist’s brain can ‘set’ the right hand to proceed at one volume while the left proceeds at another. Even when one hand has an active dynamic change going on in its line, the other hand is often steady in volume.

It’s rarer to come across a passage where a process of dynamic change in one direction is set against a dynamic change in the other direction. Such contrary voices are common in orchestral music – say, a clarinet line fading away as a cello line rises up – but not so much in piano music, where the same musician is piloting two or more lines simultaneously.

And it must be unusual to open a piece with this effect. Maybe someone will correct me, but I can’t think of an example before Chopin. He uses the effect a number of times within the piece, but to start in that way shows a thrilling kind of imagination.

0 Comments